Internet megastore Amazon is bringing a fulfillment center to the City of Union right next to the Dayton Airport, bringing in 1,500 jobs that will pay at least $15 an hour. This will be beneficial to the county and region, but these benefits are unlikely to trickle down to Dayton. Interviewees in the linked article, such as Montgomery County Administrator Michael Colbert, emphasize the strategic importance of the I-70/I-75 interchange. No doubt these two key interstates, which Dayton officials love to boast of, will soon be teeming with Amazon delivery vans. But the interchange isn’t actually in Dayton. It’s in Butler Township. And the Dayton Airport is in Vandalia. And the Amazon fulfillment center will be in Union. For the county, Amazon’s new facility is definitely beneficial, but because our local governments are so fractionalized, these benefits will be short term and hyper-localized.

This isn’t the first time a big development has brought optimism of regional benefits. Practically every Dayton suburb has has a historical moment where they thought they could have their cake and eat it, too. Benefit from the proximity of a big city without contributing to the city. Sounds great. History shows why these benefits are short-lived, fleeting, and harm the entire region.

The urban growth pattern observed in this article is also what Charles Marohn calls “The Growth Ponzi Scheme.” As he puts it, “We experience a modest, short term illusion of wealth in exchange for enormous, long term liabilities.” Every new road, sewer, water line, power line, bridge and all the other necessary infrastructure will eventually require maintenance. What happens when all that maintenance is required and tax revenue is spread out thin? Well, ever been to Detroit?

Beavercreek: A Case Study

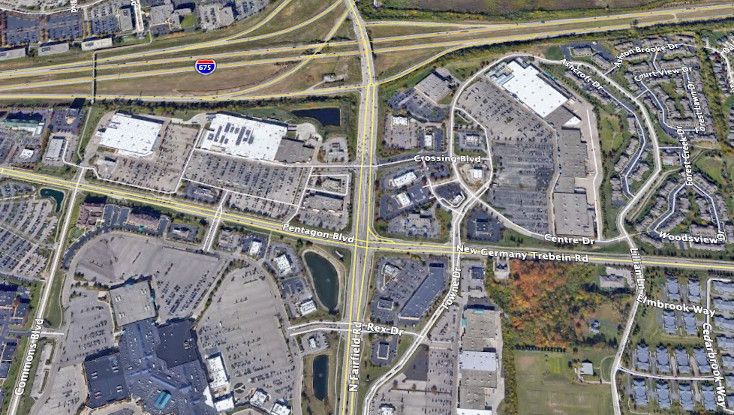

The prevailing theory among our local politicians has been that what’s good for the Dayton region is good for Dayton. When Congressman Mike Turner and the Dayton Development Coalition bring in a bunch of pork for Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, this often translates into a bunch of well-paid engineering jobs in Fairborn and Beavercreek. But does this benefit Dayton? Since the mid 90s, Beavercreek has built up enough commercial development to ensure that base employees and contractors never have to set foot in Dayton—first with the Fairfield Mall and then with The Greene. Take a look at this photo:

Image from Beavercreek Living

That’s the intersection of Fairfield Road and New Germany-Trebein Road. If you were standing at that spot on Fairfield Road today, you’d be looking at a bunch of stores such as Lowe’s, Best Buy, and Kohls. Here’s what it looks like today:

Google Earth Image

The construction of I-675 in the 1980s resulted in the rapid development of Beavercreek. The construction of the partial beltway east of Dayton was delayed because Mayor James McGee firmly opposed the construction, arguing that it would draw businesses and consumers away from downtown Dayton. From a Dayton Daily News article about McGee:

Paul Brown, a Harrison Twp. trustee from 1972 to 1980, says he and his colleagues were kept busy trying to keep Dayton from gobbling up township land and tax base through annexation.

He says McGee and other city commissioners didn’t give much consideration to the rights and desires of surrounding townships and other governments.

“McGee was very narrow-minded as far as what could advance the city of Dayton,” Brown says. “The mayor and the rest of the commission felt that if the central city died, the region died, so you’d better do what they were saying.

“I’m sure he believed what he was doing was best, but there was never much cooperation between the city and the township. That’s gotten better since the ’70s.”

McGee’s most controversial stand was his opposition of Interstate 675, the beltway connecting interstates 70 and 75 through the south and southeast suburbs.

The highway was built after McGee left office in 1982. His replacement by former mayor Paul Leonard gave I-675 supporters the third vote they needed to change the city’s position on the beltway.

“You can see what 675 did to downtown,” McGee says. “That’s what highways like that can do: They suck the vitality out of a city.”

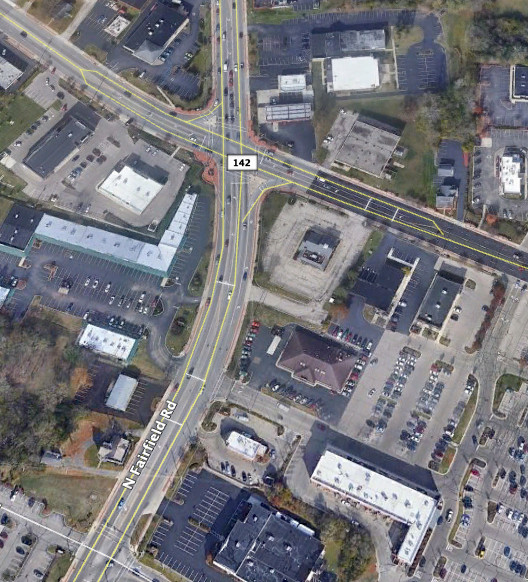

Looking back, it’s difficult to fault McGee’s logic. (It should also be noted that Harrison Township is practically fully urbanized and there’s no reason for it not to be a part of Dayton). This is what Beavercreek looked like in 1970 (the intersection of Fairfield Road and Dayton-Xenia Road):

Image from Beavercreek Living

The same intersection today:

Google Earth Image

If you’ve ever driven through Beavercreek, you may have wondered where to find downtown. Or maybe where the historic districts are. Beavercreek has the infrastructure and architecture of a city hastily erected in the last two decades of the twentieth century around a mall. Before I-675 and the Fairfield Mall, Beavercreek was a collection of township neighborhoods that primarily existed to house employees of Wright-Patterson Air Force Base. In the early 1960s, facing the threat of annexation from neighboring cities such as Fairborn and Dayton, the citizens of Beavercreek Township banded together to create the city of Beavercreek. This resulted in a long, drawn-out legal process that did not complete until 1980. They attempted to create a city that maintained the features of a township: namely, it had no income tax. Things quickly blew up:

There was an issue displaying the chart. Please edit the chart in the admin area for more details.With the creation of I-675 this tax haven of a city became a prime location for commerce and attracted the Fairfield Mall. Ironically, Beavercreek quickly became the urban center its inhabits had sought to prevent. Beavercreek thrived on retail, anchored by the mall and fueled by Wright State University and the city’s proximity to older cities such as Xenia, Springfield, Centerville, and Dayton. In the early aughts indoor malls began to lose their luster so on the south side of Beavercreek the outdoor faux-village shopping mall, The Greene Town Center, was erected. As the Fairfield Mall falls into decay and struggles to maintain tenants, the entire north side of Beavercreek has begun to look like an artifact of a bygone era. Restaurants that once enjoyed reliable clientele have closed their doors and the once-gleaming infrastructure is overdue for repairs.

Beavercreek has attempted to benefit from its proximity to Dayton and Wright-Patt while explicitly attempting to exclude the poor. Only after the Federal Government charged Beavecreek with violating the Civil Rights Act did they allow Dayton buses to make stops in the city. The message was clear: if you can’t afford a car, you’re not wanted in Beavercreek.

North Beavercreek has begun the process of decline. The surviving retail outlets and restaurants may belie the area’s stagnation to the casual observer, but its real and current trends do not bode well for its future. Meanwhile, the city, as a whole, has continued to grow at a slower pace. And although The Greene still attracts crowds, like all retail venues it faces a major threat: Amazon and the rest of the internet.

Change is the Only Constant

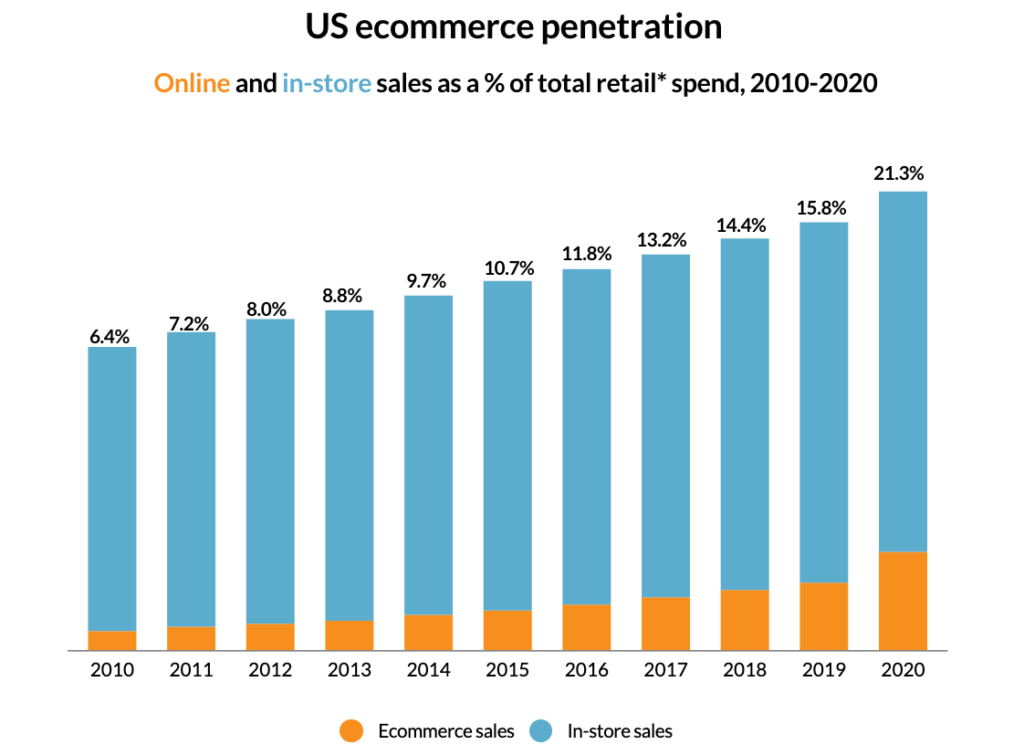

It’s no secret that Amazon has grown to massive proportions at the expense of brick and mortar retailers. The COVID-19 pandemic has supercharged this growth as people have stayed home and ordered goods from the internet. But the trend of e-commerce overtaking traditional retail had long been in the works:

Source: Digital Commerce 360

The Amazon Fulfillment center will be a boon to Union and bring many jobs to the region—but it’s also a harbinger of Beavercreek’s decline. That’s not to say that Beavercreek will fall off a cliff in the next couple of years. Its growth will stagnate. Lower-middle class families will move in hoping to enroll their children in Beavercreek’s schools. Other Beavercreek residents won’t accept these new residents and will flee to the exurbs or some other hot new development. Beavercreek will still be there. It will still be a city. But it has invested so much into infrastructure to support retail space that it will be difficult to maintain that infrastructure without those property taxes.

How can we predict this? Because that’s what always happens:

There was an issue displaying the chart. Please edit the chart in the admin area for more details.Most of Dayton’s suburbs have experienced some quick population explosion followed by long-term stagnation. The stagnation occurs when the suburb expands to its natural limitations. Briefly:

Oakwood

The 1913 Dayton flood prompted wealthy Daytonians to seek refuge on higher ground in Oakwood village. In the roaring twenties Oakwood ballooned to a city with nearly 7,000 citizens. This was because industrialist John Henry Patterson wanted to create a haven outside Dayton where wealthy white families could distance themselves from blacks and Jews while still taking advantage of their cheap labor. Oakwood’s population reached its apex in 1970 at around 10,000 people but cannot expand much beyond that because it’s wedged between Dayton and Kettering. It would take high-density housing for Oakwood’s population to eclipse its peak and such developments are antithetical to Oakwood’s existence. Nevertheless, Oakwood has maintained its niche as a wealthy white haven that contributes some of Dayton’s best talent while keeping them out of Dayton. In many ways, Oakwood is the Beverly Hills of Dayton.

Kettering

In the early 1950s Van Buren Township incorporated as the City of Kettering, starting off with a population approximately equivalent to today’s. Kettering reached its peak in the 1970s. Kettering is functionally south Dayton just as Beavercreek is east Dayton. The economy is largely anchored by healthcare and there is no room to expand. Kettering practically shares the county seat role with Dayton, as many neighboring localities and businesses treat Kettering like the county’s urban center. Due to geographical limitations, Kettering cannot continue to grow.

Moraine

Moraine is perhaps the closest analog to what Union is establishing. Originally part of Kettering, Moraine seceded in 1953 and then incorporated as a city in 1957. The city is pretty much just a giant industrial park and has grown by annexing its way into Jefferson Township. As a result, it collects tons of income taxes. According to a public record request for Moraine payroll numbers, two key things stuck out: 1) Moraine city employees get paid extremely well and 2) Moraine city employees have family members who also get paid by the city to do contract or part-time work. This is part of the problem with tax benefits going to the locality of one’s employment rather than residence: the taxes don’t benefit you and you have no say as to how they’re spent. Moraine is more of a landlord than it is an actual city.

Vandalia

Airport. Not much more to say.

Centerville, Miamisburg, Huber Heights, Englewood, West Carrollton

Like Kettering, these are white flight suburbs that all ballooned as Dayton’s population declined from the late ’70s until today. Huber Heights still has physical room for growth but after its initial expansion its population has stabilized. Like Beavercreek, they scatter services and retail to the outskirts of the Dayton metro area, weakening the inner city and requiring additional infrastructure to support their sprawl. Huber Heights and Englewood are worse than the other three, as their bloated infrastructure sprawls out of control. Centerville, Miamisburg, and West Carrollton, which began as small villages, have decent urban cores that are walkable and dense.

Riverside, Trotwood

The east and the west. Both merged with a township (Riverside was formerly known as “Mad River Township” and Trotwood was “Madison Township” in the ’90s to create more substantial cities, but neither has a useful or appealing niche. Both would benefit from merging with the City of Dayton. Clayton is similar to these as a suburban township turned city in the ’90s.

Miami Township

This is another Beavercreek. Built around the Dayton Mall and functioning as a tax haven for white collar workers. Just like Beavercreek, when the mall began to fail local officials green-lit another short-term solution that would require a boat-load of infrastructure in Austin Landing. Miami Township has a JEDD, which is a partnership with nearby municipalities that allows them to collect income tax (without a JEDD townships can only collect property taxes). This JEDD has a provision to only tax those in single-story businesses. That’s another way of saying they only tax the poor. If anything demonstrates the incompetence of government in Montgomery County, it’s this joke of a township that has been fully urbanized and leeched off our metropolitan area like a parasite. Miami Township has made a lot of money for people who do not live in this region.

Trickle-Down Regional Benefits

While additional jobs anywhere in the region is good for the region, in order for the Dayton Metro area to strategically build and maintain infrastructure and appropriately zone around that infrastructure, the region needs to be treated as a single region. The assumption that jobs in Moraine or Union will “trickle down” throughout the entire region fails to account for the fact that we’ve created a region designed so most citizens don’t have any use for the county seat. They don’t spend their money there, they don’t pay taxes there, and since the 1970s no one lives there if they can help it. This is what has happened to Dayton:

There was an issue displaying the chart. Please edit the chart in the admin area for more details.Developments in urban townships and suburbs, starting with the Dayton Mall and culminating into the regional-disaster known as Austin Landing, require more and more costly infrastructure to connect with the greater metropolitan area while only contributing taxes and economic benefits in a hyper-localized fashion. Worse yet, since this development pattern is designed to lure in chain restaurants and retailers, much of the revenue it generates is exported out of the region.

Increasingly, the sprawl effect that has harmed Dayton for decades has begun to outgrow the county. Beavercreek, as part of Greene county, has reaped the benefits of being a Dayton suburb without even contributing back to Montgomery County. Meanwhile, rapid development has quickly transformed Warren County into an urban bridge between the Dayton and Cincinnati Metro areas. While the population of the entire region is rather stagnant, it’s becoming even more thinly distributed as suburbs and exurbs expand. That means more roads, more sewers, more water, all supported with the same tax base.

Regional benefits can only be realized when the entire metropolitan area acts and governs like a single region. Otherwise, we experience a tragedy of the commons where townships become increasingly urbanized. In the beginning, great wealth and development comes from pillaging a township of its most precious resource: cheap land. Then as it becomes more urbanized, the resulting infrastructure and government becomes an encumbrance. People move further out, pillaging a new township. Rinse and repeat. That is how urban sprawl destroys a metropolitan area, by falling for a Ponzi scheme that “sucks the vitality out of a city.”

Check out this similar article from the Dayton Daily News that looks at the impact of I-675 on Dayton and how it accelerated segregation. Some of the proposed solutions, such as shared fire, EMS, police and tax revenue sharing, are moves in the right direction to thinking regionally.

0 Comments